By , Leave a Comment

What happens when the NYPD arrests you?

From first police contact to Criminal Court arraignment – learn what to do, and what not to do.

Table of Contents

A Guide to Getting Arrested in New York City

Getting arrested in New York City can be sudden and shocking:

You’re walking down the street. Police jump out of a car, screaming, with guns drawn and pointed at you. They frisk you. Slap handcuffs on your wrists. Throw you in the back seat of their car.

Or an arrest can happen with plenty of time to fill you with dread:

A detective calls. He asks you to come to the precinct on Tuesday. He says he’ll tell you what it’s about when you get there.

In any scenario, understanding the arrest process before you’re under arrest will help you:

- Be less fearful and disoriented during the process.

- Avoid making mistakes that could place you in greater legal jeopardy.

- Get released as soon as possible.

This article’s purpose is to familiarize you with the process of getting arrested in New York City.

Remember:

- Always demand a lawyer.

- Never speak with police.

- Don’t consent to anything.

- Don’t resist arrest.

- Voluntarily surrender, but leave your phone at home.

- Arrange to post cash bail at your arraignment.

Police Contact

Your first contact with police could take place under many different circumstances:

- During or immediately after an incident that occurs in the presence of police.

- During or immediately after an incident, where police arrive after someone called 911.

- At the doorway to your home, at any time (hours, days, months, etc.) after an alleged incident occurred.

- At your workplace, at any time after an alleged incident occurred.

- By phone, text, or email.

Whenever, wherever, however police approach you, the only thing you should say to police is: “I need a lawyer.”

Arrest Processes

When police arrest you in New York City, you’ll go through one of three processes: summons, desk appearance ticket (“DAT”), or full-blown arrest.

A summons is a piece of paper that a police officer hands you on the street, similar to a traffic ticket, directing you to appear in Criminal Court on a particular date. In New York City, police issue summonses for certain misdemeanors and violations. A person who receives a summons is in police custody, on the street, for a few minutes.

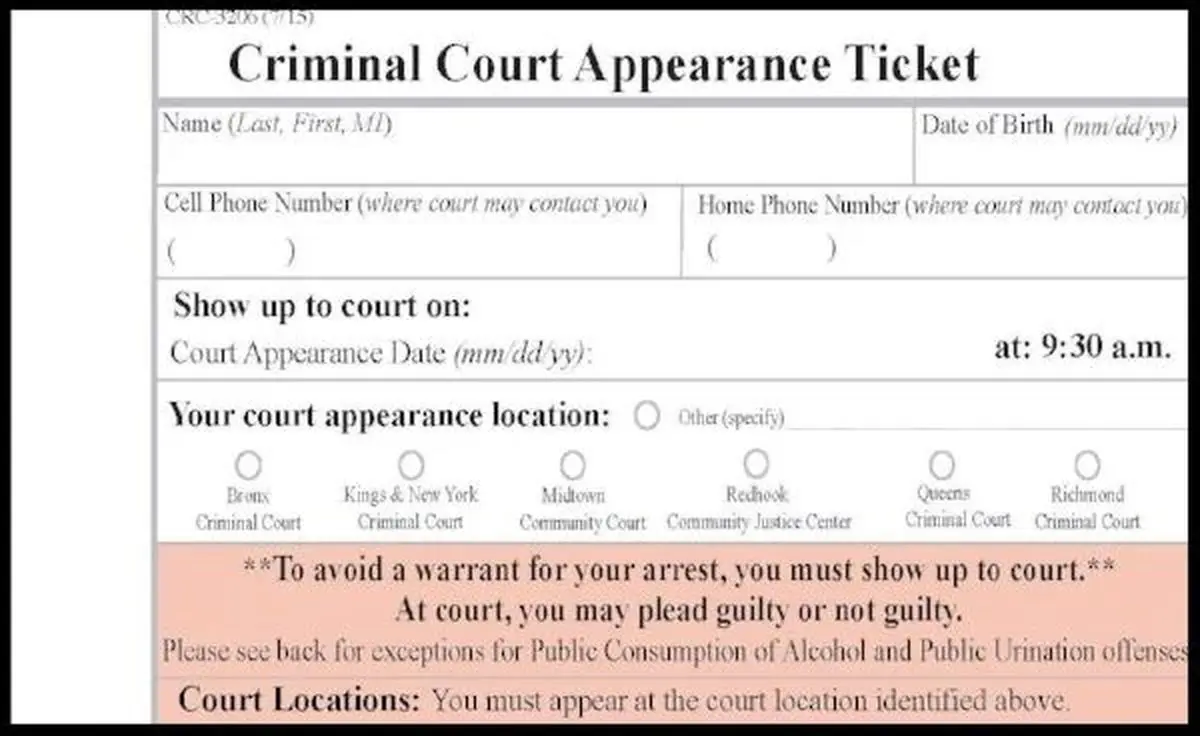

A desk appearance ticket is also a piece of paper that directs you to appear in Criminal Court on a certain date. Police may issue DAT’s for certain misdemeanors and low-level felonies. Police may not issue DAT’s to people charged with certain types of crime, such as family offenses or sex crimes. Police issue DAT’s at police station houses, not on the street. The person arrested is searched, fingerprinted, and photographed. A DAT arrest typically involves 2 to 3 hours in police custody.

As with DAT’s, full-blown arrest results in station-house custody. The person arrested is searched, fingerprinted, and arrest-photographed. Interrogation and lineups might occur. After several hours, the arrested person is transported to “Central Bookng”. There, the arrested person waits while a prosecutor drafts an “accusatory instrument” – a document filed in Criminal Court that accuses the person arrested (the “defendant”) of committing one or more crimes. Eventually, the defendant appears in Criminal Court for “arraignment“ – the court proceeding that begins a criminal case. Full-blown arrest typically involves 12 to 24 hours in custody before arraignment. If the Court sets bail at arraignment, custody continues until bail is posted.

Receiving a DAT or summons is preferable to enduring a full-blown arrest. However, DAT’s and summonses aren’t available in many cases.

Station House

New York City is geographically divided into 77 police precincts.

Precincts are numbered between 1 and 123. (Not every number in that range is assigned to a precinct.) A few precincts, such as Midtown North Precinct are more commonly known by name than by precinct number. Each precinct has a station house, which is an office building where police in the precinct work.

The NYPD website has a precinct directory, listing each precinct by number, with the station house address, the main telephone number, and a link to the precinct’s individual web page. Each precinct web page provides further details, such as additional phone numbers and the name of the commanding officer.

The NYPD website has an interactive map that locates the relevant precinct upon entering any New York City street address. After the map identifies the precinct, clicking an icon will take you to the precinct web page.

Police typically “process” arrests at the station house for the precinct where the alleged crime occurred. Processing always includes fingerprinting, taking arrest photographs, searching for i-cards, and writing up arrest paperwork. Processing sometimes includes interrogation and lineups.

A person who “voluntarily surrenders” (see below) typically meets the arresting officer at the station house covering the precinct where the alleged crime occurred.

Surrender

You might receive a phone call from a detective, asking you to come down to the police station.

The detective will tell you that he wants to speak with you. He won’t tell you that after speaking with you, he will arrest you. But now you know: after you speak with the detective, the detective will arrest you.

So never speak with the detective, or any other police officer.

While you should never speak with police, you should turn yourself in to be arrested. Turning yourself in is also known as “voluntary surrender”.

You should surrender for several reasons:

- It’s less embarrassing for you and your family than police arresting you at home .

- It’s less likely to result in losing your job, and less embarrassing, than police arresting you at your workplace.

- It eliminates the possibility of you being physically injured during a forcible arrest.

- It moves you past the most anxiety-producing stage of your case: waiting to get arrested.

- It provides you with favorable bail arguments.

Regarding number 5, after you’re arrested, a judge will determine bail conditions at an “arraignment” (your first court appearance).

Bail is a sum of money that someone must post in exchange for your release from custody, to ensure that you’ll come to court in the future. “Risk of flight” is a a major factor that courts consider when determining bail.

There might be no better argument a lawyer can make for your release without bail, or lower bail than would otherwise be the case, than: “My client, knowing she’d be arrested, voluntarily turned herself in to police this morning. Clearly, she poses no risk of flight.”

Given the opportunity, you should choose voluntary surrender.

Prepare for Arrest

If you’re going to surrender, there are several things you can do to prepare for being arrested:

Some of the most important are:

- Don’t answer your phone, unless you’re certain from caller ID that the person calling isn’t a police officer.

- Don’t bring your phone to the precinct – police might hold onto it as evidence, even if your phone is unrelated to the case.

- Only bring photo ID with you to the precinct – nothing else.

- Arrange to have someone present in court at your arraignment, with sufficient cash on hand to post your bail.

Self-Incrimination

Whether you’ve been arrested or not, your strategy with police should always be the same:

DON’T INCRIMINATE YOURSELF !!!

This simply means:

- Never speak with police.

- Don’t do anything that will make it easier for you to be convicted.

For example:

- Don’t describe “What actually happened …”

- Don’t state where you were at a certain date and time.

- Don’t admit that you know a particular person.

- Don’t consent to anything: don’t consent to police searching your home, your car, your cellphone, your bag, your pockets, etc.

- Don’t give police access to review your text messages, email, voicemail, or social media accounts.

Don’t ever lie to police,while always refusing to answer their questions.

Don’t offer physical resistance to police. If they arrest you, don’t struggle; don’t resist. If they enter your home without your permission, don’t try to physically block them.

If the police act illegally, you may challenge their actions in court. Don’t challenge them on the street or in your home:

- You’ll get injured.

- You’ll be charged with additional crimes.

At the same time, don’t cooperate with the police by answering their questions, giving them consent, or providing access to physical evidence. (An exception might or might not occur when police stop you while driving, and ask for consent to test the level of alcohol in your blood – refusal can result in revocation of your driver’s license or privilege to drive in New York for one year or more, even if your ability to drive isn’t impaired).

Not cooperating with police is difficult because:

- You may be experiencing extreme stress.

- Police will be pressuring you to give them what they want.

Fortunately, your response is simple. You only have to remember to say one thing, and to say nothing else. In response to any police question, request, or demand, your response should be:

That should be your response to every police question, request, or demand. If police ask you 1,000 questions, then answer, “I need a lawyer” 1,000 times.

Are You Arrested?

New York recognizes four levels of police intrusion. These four levels are, from least intrusive to most intrusive:

- Approaching a person to request information.

- Interfering with a person to the extent necessary to gain explanatory information.

- Forcibly stopping and temporarily detaining a person.

- Arresting a person.

The legal definition of “arrest” is not straightforward. Whether a particular police intrusion is an arrest depends on various factors.

For example, if you’re handcuffed in a police vehicle, on your way to a police station to be processed for fingerprints, arrest photos, etc., then you’re probably under arrest. However, if you’re handcuffed in a police vehicle, being transported for possible identification by an alleged crime victim, then you might not be under arrest.

On the other hand, how you interact with police mustn’t depend on whether you’re “arrested”, “temporarily detained”, “interfered with”, or “approached” by police. The lowest level of police intrusion should always place you on high alert.

Never do anything that might justify police using force against you. For example, if requested, you should place your hands where police can see them (sometimes even if not requested). You shouldn’t run away. You shouldn’t struggle with a police officer. You shouldn’t resist handcuffing.

At the same time, while you’re being physically cooperative, don’t mentally cooperate by answering questions or saying anything to police other than, “I need a lawyer.” And don’t consent to police searching your pockets, your bag, your email account, your text messages, your phone, your car, or your home.

Your Words Are Valuable – Don’t Give Them Away

Your words are extremely valuable to the police. This includes your spoken words, your written words, and your body language.

A description of your memories is evidence that only you can provide. Police want you to give them that evidence:

- What you observed with your eyes, ears and other senses.

- What you were thinking at particular moments in time.

Whether you’re innocent, guilty, or somewhere in between, police will try to use your words to convict you.

It makes no difference whether you tell the truth or a lie. It doesn’t matter whether you give a full confession, whether you truthfully admit some facts and deny others, whether you truthfully explain your innocence, or whether you completely lie.

Prosecutors will use the words that you give to police against you. They do this in one of two ways:

- Using your words as direct evidence of guilt.

- Using inconsistencies – between a) the words you use when you speak with police, and b) the words you use when you testify at trial – to prove that you’re lying.

There is no benefit to you of speaking with police. You won’t talk your way out of getting arrested, and any words you speak will be used against you. So you should never speak to police.

Miranda Warnings

You’ve probably heard of Miranda warnings, named after Arizona v. Miranda, a famous Supreme Court case from 1966.

The rule from Miranda is that while you’re in custody, police must give you the following “warnings” before asking you questions:

- You have the right to remain silent.

- Any statement you make may be used as evidence against you.

- You have the right to have a lawyer present with you.

- If you can’t afford a lawyer, a lawyer will be appointed to represent you prior to any questioning if you so desire.

Evidence obtained as a result of statements you make in response to police questioning while you’re in custody can’t be used as evidence against you, unless the prosecutor proves:

- Police gave you Miranda warnings; and

- You knowingly and voluntarily gave up your “right to remain silent” and your “right to the presence of an attorney”.

Some limitations of Miranda to keep in mind:

- If you’re not in police custody, then police may question you without giving you Miranda warnings.

- Any statement that you volunteer, unprompted by police questioning, can be used as evidence against you – even if you volunteer the statement after you demand a lawyer.

- Police violation of your Miranda rights almost never results in dismissal of a criminal case.

- If police coerce a statement from you, they will lie about having done so in court about.

NYPD procedure regarding custodial interrogation incorporates Miranda.

Whether or not you’re in police custody:

- NEVER give up your right to remain silent.

- NEVER give up your right to have your attorney present during police questioning.

Police must immediately notify a parent, or another person legally responsible for the child, when the child is in custody. If you’re present with your child while your child is in custody, police must administer Miranda warnings to both you and your child. Do not, under any circumstances, permit your child to answer police questions.

Police Interrogation

Police will manipulate you psychologically to get you to speak with them.

During an investigation, police might be respectful to you, or they might be mean. Different officers might assert different attitudes towards you (“good cop, bad cop”). Police might assert attitude directly or subtly.

However police treat you, they’re manipulating you. Always. Don’t ever forget this.

If you’re accused of a low-level offense, police might not care whether you speak.

Often, though, police are highly motivated to get you to confess. For example:

- When police suspect that you committed a crime, but don’t possess sufficient evidence to charge you.

- When the evidence against you isn’t as strong as police would like it to be.

- When you’re accused of a serious crime.

Isolation is a primary psychological technique that will police use to gain your confession: locking you away from everyone you know, in a small room, within the bowels of a police station; unable to communicate with anyone who isn’t police; dependent on police for food, water, bathroom use, sleep.

It’s unlikely that police will try to “beat a confession out of you”. However, there are many coercive measures that police will use to get you to “confess”:

- Physically intimidating you.

- Causing you to fear that you’ll remain in jail if you don’t speak.

- Falsely promising to release you (or otherwise causing you to wrongly expect to be released) if you speak.

- Causing you to fear that ACS will take your children if you don’t speak.

- Depriving you of bathroom use until they’re satisfied with the words you give them.

- Exhausting you with hours of repetitive questioning that won’t end until you speak.

- When you’re exhausted, keeping you awake, so that you’re motivated to confess by your desire to sleep.

In addition to coercion, police use a wide range of other techniques to elicit confessions, including:

- Establishing rapport with you and gaining your trust.

- Identifying contradictions in your story.

- Confronting you with evidence of guilt.

- Falsely claiming to have other evidence of your guilt.

- Offering sympathy, moral justifications, and excuses for the crime you’re accused of committing.

- Appealing to your religion or your conscience.

(Kassin, “Police Interviewing and Interrogation: A Self-Report Survey of Police Practices and Beliefs” at Table 2.)

About “falsely claiming to have other evidence of your guilt”, New York Courts have ruled that police may lie to you to get you to speak with them. For example, a defendant’s statements could be used against him in court in a case where:

“[a state trooper] told defendant that her actions were caught on video surveillance and even went so far as to place a bogus videotape on the table in front of her.”

And in a case where:

“[a police] polygraph examiner falsely informed defendant that, while she was incarcerated on unrelated charges, the police took her sneakers and matched them to prints at the scene of the crime.”

These techniques aren’t only effective at increasing the likelihood that you’ll truthfully confess to a crime that you committed. These techniques increase the likelihood that you’ll falsely confess to a crime that you didn’t commit.

Don’t falsely confess. Don’t truthfully confess. Don’t try to get police to understand what happened from your point of view. Don’t try to be transparent (“I’ve got nothing to hide”) by truthfully explaining you’re innocence. None of these things will prevent you from being arrested. Talking to police gets you nothing.

When interrogated by police, the best approach is simple: remain silent except to demand a lawyer.

Oral Statements

Some people believe that their words must be written down and signed to be used as evidence against them. This belief is absolutely wrong.

Oral statements aren’t “off the record”, even if police lead you to believe otherwise. They’re not valueless as evidence just because you didn’t write them on paper.

Police will write down your oral statements outside your presence – with varying degrees of intentional or unintentional inaccuracy – and add them to the case file.

Your oral statements are just as admissible against you in court as:

- A written statement that you signed.

- An audio recording of your spoken words.

- A video recording of you speaking.

Unlike these formally recorded statements, the accuracy of testimony about your oral statements depends on the testifying officer’s truthfulness and the quality of his memory. Your oral statements are an extremely dangerous blank slate that police can use to “remember” anything they choose about your spoken words.

Crucial details of police testimony describing your oral statements will differ from what you actually said – by a lot. The difference will not be in your favor.

Awkward Silence

It’s a good idea to anticipate the dynamics of your interaction with police, in order to avoid being manipulated.

Remaining silent in response to police questioning is socially awkward.

First, people tend to obey authority figures. Police are authority figures. Police expect civilians to submit to their authority. When you’re in custody, you’ll feel the weight of this expectation. So, when police ask you questions, you might feel naturally inclined to answer.

Don’t.

Second, etiquette compels us to courteously answer questions. It’s rude to ignore anyone who asks a question, not just a police officer.

Because we’re trained throughout our lives to answer questions, especially questions posed by authority figures, remaining silent when questioned by police feels awkward. Especially if the police handling your case are nice to you.

Whether locked in an interrogation room at a police station, stopped on the street, confronted at your front door, or called on the phone – you’ll feel inclined to answer police questions. You’ll feel yourself automatically begin to respond. It’s human nature.

You might be especially inclined to answer police questions if you’re thinking, “I know I didn’t do anything wrong. Let me clear up their confusion.”

Never try to clear up police confusion:

If police have a basis to arrest you before you speak with them, then they will arrest you regardless of what you say.

If police don’t otherwise have a basis to arrest you, then your refusal to speak with them can’t give them a basis to arrest you.

Clearing up confusion won’t benefit you. So don’t do it.

Always be on guard when confronted by police. They’re tricky. The officer who arrests you might initiate pleasant conversation about things unrelated to the investigation. Although you’ll feel awkward or rude saying nothing in response: say nothing in response. Otherwise, an innocuous conversation about the weather will inevitably morph into a conversation about whatever it is they’re investigating.

After developing a rapport with your interrogator, saying nothing becomes more difficult. Nip it in the bud.

Other than demanding a lawyer, remain silent in response to all police efforts to initiate conversation. You’ll feel rude. Do it anyway.

State of Mind

When police first attempt to question you:

- You might know exactly what they want to discuss with you.

- You might have no idea what they want to discuss with you.

- You might think you know what they want to discuss with you, but be wrong.

- You might have no memory, or a distorted memory, of whatever they want discuss with you, due to intoxication or other reasons.

Regarding the incident that police are investigating:

- You might be innocent.

- You might be innocent, but feel that certain facts make you look guilty.

- You might be guilty, but not realize it because you don’t fully understand the law.

- You might know that you’re guilty.

- You might not know whether you’re innocent or guilty because you have no memory of the incident being investigated.

- You might be misled by police to believe that they’re investigating one incident, when they’re actually investigating something else.

You won’t know what information the police have about the crime they’re investigating: other witnesses, phone records, text messages, emails, voice messages, surveillance video, cell tower records, DNA, etc. The police will not reveal this information to you. If they appear to reveal evidence, they might be lying. If they claim not to know certain information, they might be lying.

Ultimately, what you know and don’t know, and whether or not you’re innocent – none of that mattera. You’re going to remain silent, except to demand a lawyer.

As you listen to police questions, you might consider:

- Truthfully answering every question that the police ask you.

- Lying in response to certain questions – not because you’re guilty, but because you think that truthful answers would erroneously make you appear to be guilty, or because truthful answers would incriminate someone you care about.

- Outright lying to try to mislead the police and conceal your guilt.

- Remaining silent, except to demand having a lawyer present.

Only one of these four options is always the correct option. (Hint: “4. Remaining silent, except to demand having a lawyer present.”)

Demand a Lawyer

“I need a lawyer.” Always say it when police confront you.

Police are trained to interrogate you.

You are not trained to answer police questions.

Police want you to tell them everything you know, without telling you anything they know.

There are many responses to each question that you might be tempted to give, ranging from truth to lies. You are disoriented and confused; tired and uncomfortable; anxious and scared. Police are urging you to provide definite answers when you’re memory might not be clear.

Fortunately, your response is simple. Answer every question with, “I need a lawyer”.

If you realize you’ve been duped into answering some questions, stop answering. Immediately. You can’t un-say what you already said, but say no more. Answer every question thereafter by demanding a lawyer.

Central Booking

When police finish processing you at the station house, the arresting officer will take you to “Central Booking”.

Central Booking is a countywide detention facility maintained by the NYPD. Each county has its own Central Booking facility, consisting of several large holding cells connected to the courthouse where your arraignment will occur. Arrestees from all precincts throughout the county wait at Central Booking before seeing a judge.

While you wait at Central Booking, the District Attorney writes up an “accusatory instrument” that accuses you of one or more crimes.

After the District Attorney files an accusatory instrument in your case, you will appear before a judge for arraignment.

Arrest Number

Each time an NYPD officer arrests someone in connection with an alleged crime, the NYPD generates a unique “arrest number”.

The arrest number identifies one arrest of one person for one incident. If multiple people are arrested in connection with one incident, the NYPD assigns a separate arrest number to each person arrested. If one person is arrested in connection with multiple incidents, the NYPD will assign a separate arrest number to each incident.

While you’re in custody, the NYPD keeps track of you by your arrest number.

When your friends and family ask the Court about whether your case is ready go before the judge for arraignment, court clerks who look up the status of your case might ask for your arrest number.

Your family might be able to get your arrest number from the arresting officer, or the station house that processed your arrest. However, the clerks should be able to look up the status of your case when provided with your name and date of birth.

District Attorney

Each of New York City’s five counties has its own District Attorney.

State crimes allegedly committed in Manhattan are primarily prosecuted by the New York County District Attorney; in Brooklyn, by the Kings County District Attorney; in Queens, by the Queens County District Attorney; in the Bronx, by the Bronx County District Attorney; and in Staten Island, by the Richmond County District Attorney.

The Special Narcotics Prosecutor of the City of New York conducts state felony narcotics investigations and prosecutions in all five boroughs.

The New York State Attorney General has statewide jurisdiction, and prosecutes certain state crimes allegedly committed in New York City.

Federal crimes allegedly committed in New York City are prosecuted by the US Attorney for the Southern District of New York (Manhattan, and the Bronx); and the US Attorney for the Eastern District of New York (Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island).

Court

Two types of court have jurisdiction over state criminal cases in New York City: Criminal Court and Supreme Court. Each borough/county has its own courthouses for Criminal Court and Supreme Court.

The address and telephone number of each New York City Criminal Courthouse is online: Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, Bronx, Staten Island, Midtown Community Court, Red Hook Community Court, and the Summons Courts.

The address and telephone number of each Supreme Courthouse in New York City is also online: Manhattan (locations and telephone numbers), Brooklyn, Queens, Bronx, and Staten Island.

New York has two major categories of crime:

- Misdemeanors – less serious crimes that carry a maximum penalty of one year in jail or less.

- Felonies – more serious crimes that carry a maximum penalty of more than one year in jail.

Cases in which the most serious charge is a misdemeanor go to Criminal Court.

In New York, you can only be convicted of a felony in Supreme Court. You can’t be convicted of a felony in Criminal Court. Before you can be convicted of a felony in Supreme Court, a “grand jury” must vote to file an “indictment” against you.

Some people arrested on felony charges in New York City are indicted before police arrest them. Their cases go directly to Supreme Court.

The majority of people arrested on felony charges in New York City are not indicted before police arrest them. Their cases all go to Criminal Court, where they remain unless they are indicted. Upon indictment, these cases are transferred to Supreme Court.

Arraignment

Arraignment is the court proceeding that begins the “criminal action” against you. The criminal action against you will be called, “The People of the State of New York v. [Your Name]”.

Unless you receive a summons or a desk appearance ticket, arraignment usually occurs sometime between 12 and 24 hours after police arrest you. Arraignment is your first appearance in court following a full-blown arrest.

Most often, arraignment occurs in Criminal Court.

In New York City, District Attorneys commence criminal actions by filing an “accusatory instrument” (a piece of paper accusing a defendant of one or more crimes) in Criminal Court, or by filing an indictment in Supreme Court.

The different types of accusatory instrument that may be filed in Criminal Court are called:

- an “information”;

- a “simplified information”;

- a “prosecutor’s information”;

- a “misdemeanor complaint”; or

- a “felony complaint”.

At your Criminal Court arraignment on misdemeanor charges, the Court must

- Immediately inform you of the charges against you.

- Provide you with a copy of the accusatory instrument filed against you.

- Release you without bail, or set bail to secure your future appearance in court.

At your Criminal Court arraignment on a felony complaint, the Court must:

- Immediately inform you of the charges against you.

- Provide you with a copy of the felony complaint.

- Either release you without bail, set bail to secure your future appearance in court, or “remand” you (hold you without bail).

At your Supreme Court arraignment on an indictment:

- The Court must immediately inform you of the charges against you.

- The District Attorney must provide you with a copy of the indictment.

- The Court must either release you without bail, set bail to secure your future appearance in court, or remand you.

Docket Number

Each case in Criminal Court is assigned a unique identifying number called a “docket number”. Your docket number is generated by the Clerk’s Office. This is one of the last things that happens before your arraignment.

Each case in Supreme Court is assigned a unique “indictment number” or, less commonly, an “SCI (‘Superior Court Information’) number”.

Shortly after your case is filed in court, information about your case is publicly available online in a database on the court system’s website called WebCrims. There, anyone can look up your case by entering your name into the database.

The data within WebCrims is not directly accessible using a regular search engine: if someone does a Google search of your name, your case’s WebCrims entry will not appear within the search results. Searchers must enter the WebCrims site and search your name within its database there to find WebCrims search results.

Your name remains publicly accessible in WebCrims, to you or anyone else, only while your case is pending with a future court date. When your case is finished, your name no longer will be accessible within WebCrims (but it will be accessible in other databases if you’re convicted of a crime). If you fail to appear in court and a judge issues a bench warrant, your name no longer will be accessible within WebCrims.

Bail

“Bail” is property (cash or bail bond) held by the Court in exchange for releasing you from custody. The purpose of bail is to make sure you come to court when required.

If you miss a court date, then the person who posted your bail will forfeit their money. The City will keep it.

At the end of your case, if you have attended all your court appearances, then the City will return your bail (minus an administrative fee) to the person who posted it.

At your arraignment, the Court must decide whether to:

- Release you on recognizance (“ROR”);

- Set bail; or

- Remand you (hold you without bail).

If you’re ROR’d, then 👍🏽 you don’t have to worry about posting bail. You walk out of the courtroom and remain at liberty while the case is pending.

If you’re committed to the custody of the sheriff, then you can’t post bail.

If the Court sets bail, typically you’ll be allowed to post it as “cash bail” or by “bail bond”.

Cash bail is a sum of money that a family member or friend pays in cash on your behalf, in exchange for you being released from custody.

Sometimes, the Court will let you post bail by credit card, up to a maximum of $2,500. Credit card bail may be posted at the courthouse immediately after your arraignment. Beginning several hours after your arraignment, credit card bail may be posted online and at City jails.

A bail bond is a document that obligates an insurance company to forfeit a fixed sum of money to the state if you don’t return to court. Bail bonds may be purchased through bail bond agencies. In New York City, bail bond agencies typically have offices within walking distance of the Criminal Courthouses in each borough.

When determining bail, the Court may consider many factors, including:

- Your employment and financial resources.

- Your family ties and length of residence in the community.

- Your criminal record, or lack of criminal record.

- Your bench warrant history.

- Whether you tried to avoid arrest.

- The strength of the criminal case against you.

- The potential jail sentence you could receive if convicted.

The theory is that each of these factors makes you more or less likely to return to court. For example, an accused person facing mandatory jail time if convicted is more likely to come back to court if bail is set than if no bail is set.

A June 19, 2018 FiveThirtyEight.com article details the bail-setting practices of New York City Criminal Court judges who arraigned Legal Aid clients on felony complaints during 2017. The likelihood of receiving ROR varies depending on the judge who arraigns you and, to a lesser extent, the borough where you’re arraigned.

Cash Bail

If you know that you’re going to be arrested, you should immediately plan to have someone post cash bail in the courthouse at your arraignment.

Even if you know that the Court probably will ROR you, you should arrange in advance to have someone post cash bail at your arraignment.

When the Court sets bail, if someone immediately posts cash bail or credit card bail in the courthouse, then you’ll walk out of the courtroom within 15-30 minutes after bail is set.

If the Court sets bail, and no one posts bail in the courthouse, then you’ll be held at a New York City jail until someone posts your bail at one of the City jails. This can increase the amount of time that you spend in custody by half a day, and often much longer.

So, whenever possible, arrange to have someone post cash bail for you at your arraignment.

Free Consultation

Bruce Yerman is a New York City criminal defense attorney. If you’ve been accused, contact Bruce for a regarding arrest or anything else that concerns you.

Leave a Reply