By , Leave a Comment

Table of Contents

Indictment

Before bringing a defendant accused of a felony to trial, a prosecutor must go through a grand jury proceeding to obtain an “indictment”.

An indictment is a piece of paper. In it, a “grand jury” formally accuses one or more people of committing crimes.

An indictment may be filed after an accused person is arrested and arraigned, or before.

A prosecutor must indict before bringing an accused person to trial on felony charges.

Grand Jury

Grand juries are made up of regular citizens – groups of people serving jury duty.

Instead of sitting in a courtroom listening to evidence presented at a trial, grand jurors sit in a “grand jury room” and listen to evidence presented at a “grand jury proceeding”.

The purpose of a grand jury proceeding is to determine whether the district attorney has enough evidence to take an accused person to trial on felony charges.

After hearing evidence, a grand jury can take various actions according to the law. The two primary actions a grand jury can take are: 1) voting “a true bill” (indicting); or voting “no true bill” (not indicting).

Differences between Grand Juries and Trials

Though jurors participate at both grand jury proceedings and trials, the two proceedings are very different. The grand jury’s function is perhaps best explained by describing some of those differences:

- Unlike trials, where judges preside and rule on questions of law, no judge is present while evidence is presented at the grand jury. Lacking a judge, the district attorney serves as “legal advisor” of the grand jury.

- Unlike trials, which are conducted openly in public courtrooms, grand jury proceedings are conducted in secret. Only people authorized by statute may be present, such as: grand jurors, assistant district attorneys, a clerk, a stenographer, court officers, a testifying witness, and, sometimes, a lawyer for the witness.

- Unlike trials where the accused is present at every stage of the proceedings, at the grand jury, the accused isn’t present at all, with one exception: the accused is present if he or she testifies. Whether or not he testifies, the accused doesn’t know the identity of any witness who testifies against him; the accused doesn’t get to hear any testimony; and the accused doesn’t get to cross-examine the other witnesses. (Cross-examination involves questioning the other side’s witness, in an effort to prove that the witness is mistaken, lying, or otherwise unreliable.) And while the accused never gets to cross-examine witnesses in the grand jury, the district attorney gets the opportunity to cross-examine the accused.

- Unlike trials, where the district attorney must establish proof “beyond a reasonable doubt” to get a conviction, at the grand jury, the district attorney must only establish “reasonable cause to believe that such person committed such offense” to indict the accused. Think of “beyond a reasonable doubt” as 99 percent certainty; think of “reasonable cause” as 51 percent certainty (although it’s really less than that).

- Unlike trials, where, to get a conviction, the district attorney must unanimously persuade all 12 jurors of guilt, at the grand jury, to get an indictment, the district attorney must only persuade 12 of 23 grand jurors (a little more than half).

Much Easier for DA to Get Indictment than Conviction

District attorneys have much less difficulty getting grand juries to indict than getting trial juries to convict: a district attorney must persuade only some jurors of guilt, much less convincingly than at trial, based on uncontested evidence, at a secret proceeding where the district attorney acts not only as advocate, but in a role similar to that of a judge.

Indictment is a necessary preliminary step that the DA must take before having the right to bring the accused to trial on felony charges.

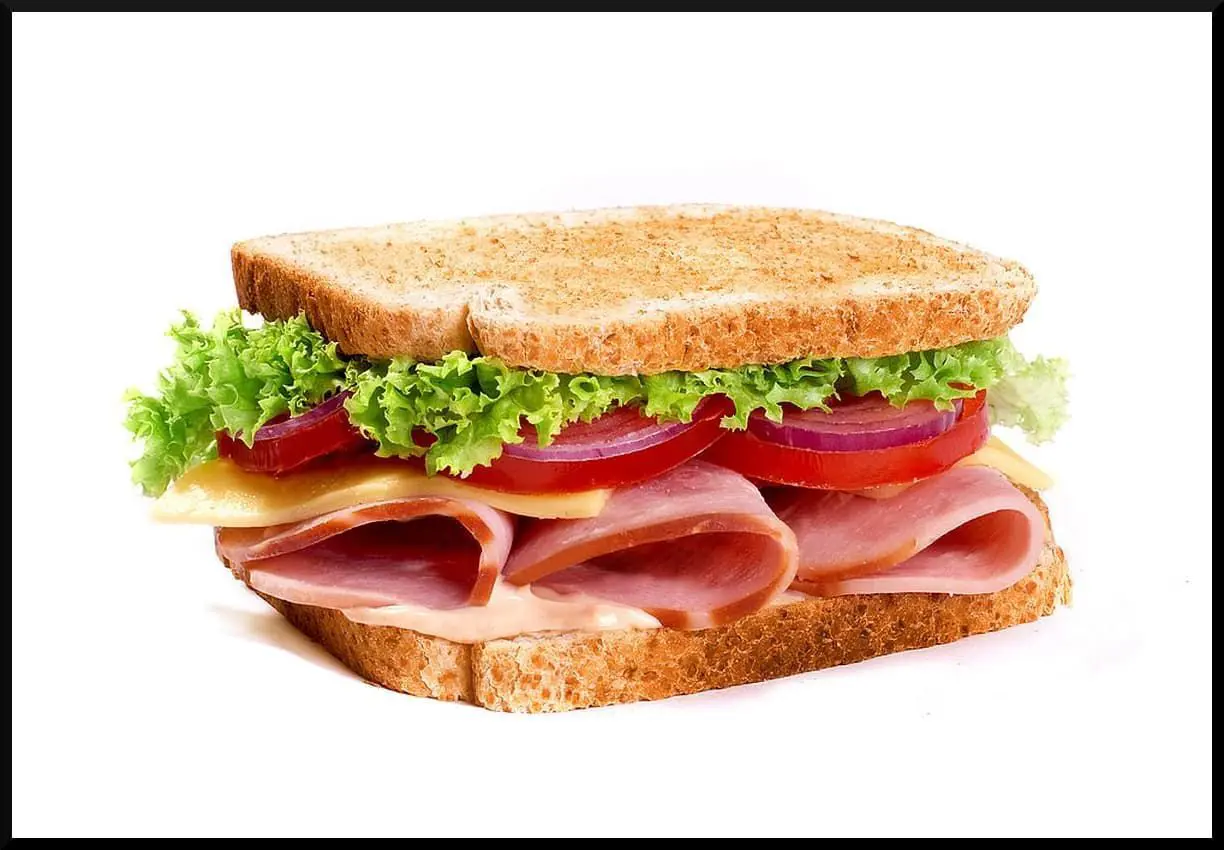

Sol Wachtler, former Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals, once famously stated, “Any prosecutor who wanted to, could indict a ham sandwich.”

Fortunately, the grand jury acts only at the preliminary stage of a criminal proceeding. When a grand jury proceeding occurs, it’s in addition to – never instead of – a trial.

Indictment does not equal conviction. Not even close.

Free Consultation

Bruce Yerman is an criminal defense attorney in New York City. His office is located in Suite 1803 of 299 Broadway in Manhattan.

If you’d like a free consultation to discuss grand jury proceedings or any other issue related to criminal defense or family law, call Bruce at:

Or email Bruce a brief description of your situation:

Leave a Reply