By , Leave a Comment

Table of Contents

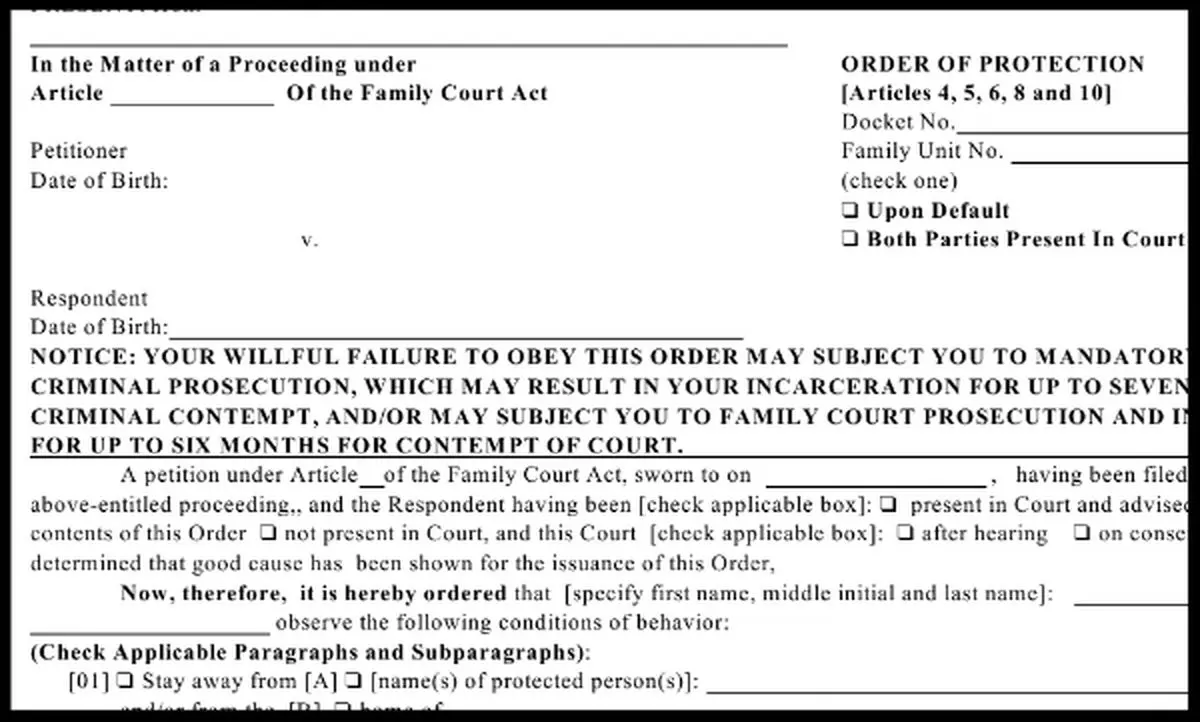

What’s an Order of Protection?

An order of protection is a court order that directs one person (the “subject”) to avoid behavior directed at another person (the “protected person”).

For example, an order of protection might direct John Doe to stay away from, and refrain from communicating with, Jane Doe.

Issued in Multiple Courts

Criminal courts issue orders of protection in virtually all domestic violence (“DV”) cases, and in many non-DV cases involving allegations of violence, threatened harm, stalking, or harassment.

Family Court also issues orders of protection where domestic violence is alleged: in family offense proceedings, child protective proceedings, and custody proceedings.

The Civil Term of Supreme Court issues orders of protection in divorce proceedings that involve accusations of domestic violence.

AKA “Restraining Orders”

Orders of protection are often called restraining orders. However, they’re just one type of restraining order.

“Restraining order” is a broader term that includes “injunction”. Criminal courts and Family Court can’t issue injunctions.

Criminal Penalties

If you’re the subject of an order of protection, think of the order as a penal law that applies only to you. If you violate that law, you could be convicted of a crime.

You can be convicted in a criminal court even if the order came from Family Court or divorce court.

Intentionally failing to obey an order of protection is a crime called “criminal contempt in the second degree”, a misdemeanor that carries a maximum sentence of 1 year in jail.

“Criminal contempt in the first degree” is a felony that carries a maximum sentence of 4 years in jail. It can be committed by:

- Intentionally failing to obey an order of protection, after having been convicted of criminal contempt in the previous 5 years; or

- Violating an order of protection:

- by intentionally placing or trying to place the protected person in reasonable fear of physical injury or death by displaying a weapon or what appears to be a firearm, or by making a threat; or

- by intentionally placing or trying to place the protected person in reasonable fear of physical injury or death by stalking the person; or

- by intentionally placing or trying to place the protected person in reasonable fear of physical injury or death by communicating by telephone, text, email, social media, mail, or any other form of written communication; or

- with intent to harass, annoy, threaten or alarm a protected person, repeatedly making telephone calls to such person, whether or not a conversation ensues, with no purpose of legitimate communication; or

- with intent to harass, annoy, threaten or alarm a protected person, striking, shoving, kicking, or otherwise subjecting the person to physical contact, or attempting or threatening to do the same; or

- by physical menace, intentionally placing or attempting to place a protected person in reasonable fear of death or physical injury; or

- by intentionally or recklessly damaging the property of the protected person in an amount exceeding $250.

Aggravated criminal contempt is a felony that carries a maximum sentence of 7 years in jail. It can be committed by:

- Committing the crime of criminal contempt in the first degree after having been convicted of criminal contempt in the first degree within the preceding 5 years.

- Violating an order of protection by intentionally or recklessly causing physical injury to the protected person.

- Committing the crime of criminal contempt in the first degree after having been convicted of the crime of aggravated criminal contempt.

Due to the serious penalties, people shouldn’t make frivolous domestic violence complainants.

Temporary Orders of Protection

A “temporary order of protection” (“TOP”) is issued during litigation, usually at the beginning. A “final order of protection” is issued at the end.

In criminal cases, TOP’s are typically issued at arraignment. In DV cases, they’re issued virtually 100% of the time. In non-DV cases, less often.

In Family Court proceedings, judges often issue TOP’s with only the protected person present. The subject has no opportunity to oppose. (This one-sided process is called ex parte.) An ex parte TOP application in Family Court typically occurs when the protected person files a family offense petition, alleging that the subject committed a “family offense” against a “member of the same family or household”.

Divorce courts sometimes issue ex parte TOP’s when one spouse alleges domestic violence against the other. The TOP effectively awards “exclusive occupancy of the marital residence” to the protected-party spouse by kicking out the subject spouse.

Criminal courts may issue ex parte TOP’s simultaneous with arrest warrants.

A subject usually has no knowledge of an ex parte TOP until the subject is served with a copy. The subject can’t be liable for contempt unless the subject is aware that the TOP exists. Typically, this occurs in court, when a judge orally describes the TOP to the subject – or outside of court, when a police officer, marshal, or process server delivers a copy of the written TOP to the subject.

A TOP might expire on the next court date, or on some other specific date – for example, 6 months after it’s issued.

A TOP issued with a warrant will remain in effect indefinitely, until the subject appears in court and vacates the warrant.

Where the case underlying a TOP is dismissed before the TOP expires, the TOP immediately becomes ineffective, regardless of the subsequent expiration date.

Final Orders of Protection

Criminal courts issue final orders of protection upon conviction, whether by guilty plea or trial, with the order lasting up to:

- 2 years upon conviction of a “violation”, an “unclassified misdemeanor”, or a “class B misdemeanor”.

- 5 years upon conviction of a “class A misdemeanor”.

- 6 years upon conviction of “misdemeanor sexual assault” when the court has imposed a 6-year term of probation.

- 8 years upon conviction of a “felony”.

- 10 years upon conviction of “felony sexual assault” when the court has imposed a 10-year term of probation.

DV cases that result in dismissal or acquittal are the only criminal court DV cases that are resolved without a final order of protection. Virtually every other DV case results in a final order of protection of some kind.

Family Court may issue a final order of protection during a family offense proceeding, at the conclusion of a “dispositional hearing”. The order may remain in effect for up to:

- 2 years; or

- 5 years, upon a finding of “aggravating circumstances”.

Family Court may extend a final order of protection for a reasonable period of time, upon a showing of good cause, or upon consent of the parties.

Limited vs. Full

An order of protection directs the subject to obey certain conditions, such as:

- Stay away from the home, school, business or place of employment of the protected person.

- Refrain from committing a “family offense” against the protected person.

- Refrain from harassing, intimidating or threatening the protected person.

- Refrain from communicating with the protected person by any means, including through third parties.

An order that imposes all these conditions is often referred to as a “full order of protection” or a “no-contact order of protection”.

A less-restrictive order – solely directing the subject to refrain from committing family offenses against the protected person, and to refrain from harassing, intimidating, or threatening the protected person – is often referred to as a “limited order of protection” or a “no-harass order of protection”.

In domestic violence cases, criminal courts routinely issue full orders of protection at arraignment. Upon conviction, with the DA’s consent, the Court might issue a limited order of protection. Sometimes, the Court will issue a limited order of protection while a case is pending.

Typically, criminal courts issue limited orders only where the protected person advocates for a limited order – or no order – with the DA.

The lack of contact required by a full order of protection can place enormous financial stress on parties who live together. A full order directs the subject to stay away from the protected person’s home, which requires cohabiting couples to pay the expense of two residences.

Often, while a full TOP is in effect, the DA will offer a limited final order of protection, as leverage to force a guilty plea: the full order will continue to harm the affected family unless the defendant accepts the offer.

Loss of Firearms Rights

Temporary orders of protection issued by criminal courts and Family Court always:

- Suspend any existing firearms license possessed by the subject.

- Order the immediate surrender of all firearms, rifles, or shotguns owned or possessed by the subject.

- Order that the subject is ineligible for a firearms license.

Final orders of protection issued by criminal courts and Family Court always:

- Revoke or suspend any existing firearms license possessed by the subject.

- Order the immediate surrender of any or all firearms, rifles, or shotguns owned or possessed by the subject.

- Order that the subject is ineligible for a firearms license.

Firearms licenses are very difficult to obtain in New York City. As a practical matter, even if the case against you is dismissed, an order of protection issued in a DV case may prevent you from ever being licensed to possess a firearm in NYC.

Subsequent Family Court Orders

The subject of a full order of protection might have children in common with the protected person.

If a criminal court order bars the subject from communicating with the protected parent of children that the parties have in common, then the subject is effectively barred from parenting the parties’ children – the subject can’t speak with the protected parent to arrange visitation.

Criminal court orders of protection usually permit Family Court and Supreme Court to issue subsequent orders that would permit communication necessary to facilitate custody and visitation. The subsequent orders might also permit the subject to pick up and drop off the children at the protected person’s home. Acquiring such an order requires the subject to commence a custody proceeding, unless one is already begun.

If the parties have a custody order that predates an order of protection, then the subject must return to Family Court or Supreme Court to get a new custody order.

Protected Person Can’t Violate

A protected person can’t violate an order of protection issued for the protected person’s benefit. Only the subject can.

Orders of protection must include the following notice to police: “The protected party cannot be held to violate this order nor be arrested for violating this order.”

There are many ways to get caught violating an order of protection. Don’t try to outsmart the system.

Protected Person Can’t Modify

Only courts have authority to modify or terminate orders of protection.

Protected parties have no authority to permit subjects to violate orders of protection.

If you’re prosecuted for violating an order of protection, for example, by being in the protected person’s home, it’s no defense to claim that the protected person invited you there.

Criminal court orders of protection contain the following notice in capital letters: “This order of protection will remain in effect even if the protected person has, or consents to have, contact or communication with the party against whom the order is issued.”

Brief Opportunity to Retrieve Property

Where the subject and the protected person live together, the subject’s lawyer should ask the Court to grant the subject permission to retrieve property from the parties’ joint residence. Courts typically grant such requests.

However, the Court will order that:

- The subject must be accompanied by police; and

- Retrieval of property may occur only on a particular date, between certain hours.

Some practical pointers for subjects:

- Go to the police precinct at least 15 minutes before the retrieval period begins, because you might have to wait a while before officers are available to accompany you. (For example, if the TOP says you can retrieve property between noon and 6:00 p.m., then go the precinct at 11:45 a.m.)

- The police will give you about 10 minutes to get your stuff, so think carefully in advance about everything you need to retrieve, and where it’s located, so you can retrieve it efficiently.

- The police will not help you locate or carry property.

- Bring sufficient containers to carry your property away from the residence.

- Bring a friend or two to help you carry your property.

- If the protected person disputes your right to take a particular item of property, the police won’t let you take it.

- You won’t get another chance to get your property from the marital residence until the next court date, so think carefully about the items that you’ll retrieve. Make a list that includes:

Incidental Contact

If the subject and the protected person work together, or attend school together, or if the subject must visit a family member who resides in the same apartment building as the protected person, then the Court might allow “incidental contact” at a specific location.

If the parties work for the same company, for example, permitting incidental contact would allow the subject to perform job duties at the same premises as the protected person.

If you’re the subject of an order of protection with an incidental-contact clause, don’t speak with the protected person. Also, avoid being in close proximity to the protected person – for example, don’t get on the same elevator. Don’t get on the same bus or subway car to and from work.

If you and the protected person must communicate at work, then seek an order of protection that specifically allows such communication. Don’t rely on a generic incidental-contact clause.

Avoid Butt Dialing

If you’re the subject of an order or protection, and you inadvertently contact the protected person, police will believe you did it intentionally.

Take steps to avoid butt dialing and other unintended communication:

- Clear the call history from your phone.

- Remove the protected person’s name, phone numbers, and email addresses from all your contact lists, text apps, email apps, and social media apps.

- Unfriend the protected person from your social media.

- Remove your name from all groups and email lists in which you and the protected person are both enrolled. You don’t want a group email authored by you to appear in the protected person’s mailbox.

- Don’t discuss the protected person on social media.

Free Consultation

Bruce Yerman is a domestic violence lawyer in New York City. His office is located in Suite 1803 of 299 Broadway in Manhattan.

If you’d like a free consultation to discuss criminal defense or family law, call Bruce at:

Or email Bruce a brief description of your situation:

Leave a Reply