By , Leave a Comment

Table of Contents

People v. Berrezueta

The June 7, 2018 Court of Appeals decision People v. Berrezueta relates to the original blog entry.

“Switchblade knife” is defined by law as: “any knife which has a blade which opens automatically by hand pressure applied to a button, spring or other device in the handle of the knife.” NY Penal Law Section 265.00(4).

In People v. Berrezueta, New York’s highest court held that:

[T]he evidence presented at trial by the People, which included the police officer’s testimony and his demonstration of the operability of the knife, was sufficient to support the factfinder’s conclusion that the knife found on defendant’s person met the statutory definition of a switchblade.

Some commentators have expressed alarm that Berrezueta expands the definition of switchblade to include knives that open automatically by hand pressure applied to a button, spring or other device in the blade of the knife, not just in the handle.

However, the Court of Appeals did not address this issue in Berrezueta. The Court merely affirmed the Appellate Term’s affirmation of the defendant’s conviction. Neither the Court of Appeals nor the Appellate Term describe the knife in issue as having a button or other device in the blade rather than in the handle.

Only the dissenting opinion of the Hon. Jenny Rivera describes the knife in these terms, but the dissenting opinion doesn’t control, the majority decision does.

Judge Rivera describes the following references to the knife in the trial record:

- A “United States Army-themed knife.

- “The knife has a “spring mechanism” located “in the blade”.

- The knife opens by “put[ting] pressure on the button, spring loaded inside, the spring opens the knife and locks the blade in place.”

- The knife has a button “on the side of the knife”.

- The button is “[a]ttached to the blade”.

- But also, the button was “on the handle” and “not on the blade”.

- To open the knife the “thing you press … moves to above the handle.”

- “[T]he button moved with the knife’s blade away from the handle when the knife opened”.

- Defendant testified that he always opened the knife a second way, “like a box cutter ‘with the control of [his] thumb’, ‘instead “always use[ing] the knob.'”

- “Pictures of the knife introduced into evidence confirm that the activating button is on the blade, not ‘in the handle.'”

The majority does not acknowledge any of these facts in its decision.

Judge Rivera would have reversed Mr. Berrezueta’s conviction of criminal possession of a weapon in the fourth degree, because “the evidence failed to establish that the knife ‘has a blade which opens automatically by hand pressure applied to a button, spring or other device in the handle of the knife'”.

The standard of review that the Court of Appeals applies when reviewing sufficiency of evidence is: “whether after viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to the prosecution, any rational trier of fact could have found the essential elements of the crime beyond a reasonable doubt.”

This standard for reversal due to insufficient evidence is very difficult to meet. In Berrezueta, the Court of Appeals would have had to find, based on the evidence presented at trial, that the Trial Court’s decision to convict the defendant was irrational.

The Berrezueta majority is saying: looking at the evidence in the light most favorable to the DA, a rational judge could have found beyond a reasonable doubt that the knife was a switchblade. The majority doesn’t describe the evidence and apply the law to explain how it arrived at this conclusion. The majority merely concludes that the Trial Court’s decision WASN’T irrational.

Judge Rivera is saying the opposite: looking at the evidence in the light most favorable to the DA, a rational judge could not have found beyond a reasonable doubt that the knife was a switchblade. Unlike the majority, Judge Rivera analyzes the evidence presented to the Trial Court, describing how she arrived at her conclusion. Judge Rivera finds that the conviction of Mr. Berrezueta is rational only if the definition of “handle” is expanded to include “blade”. However, since courts have no authority to change the statutory definition of “handle”, Judge Rivera concludes that the Trial Court’s decision WAS irrational.

While Judge Rivera argues that the majority’s decision must hinge on changing the definition of “handle” to encompass “blade”, the majority decision itself makes no reference to how the majority interpreted the definition of handle.

Since the majority decision doesn’t state or imply that “handle” encompasses “blade”, Berrezueta shouldn’t be interpreted as announcing such a rule.

I wouldn’t recommend that a civilian in New York carry a spring-assisted knife with a thumb-stud or other opening device attached to the blade. The risk is too great. You could be be wrongly charged and convicted.

Having a prior criminal conviction should provide even greater incentive not to carry such knives. The prior conviction aggravates what otherwise would be a misdemeanor to a felony, increasing the maximum sentence from one year in jail for the misdemeanor, to seven years for the felony.

However, under the Penal Law, a knife with a thumb-stud or other device attached only to the blade is not a switchblade. Berrezueta hasn’t changed the law. If charged, you should still assert the not-a-switchblade defense. The original blog entry appears below:

Arrest

Police arrested my client for allegedly possessing a switchblade knife.

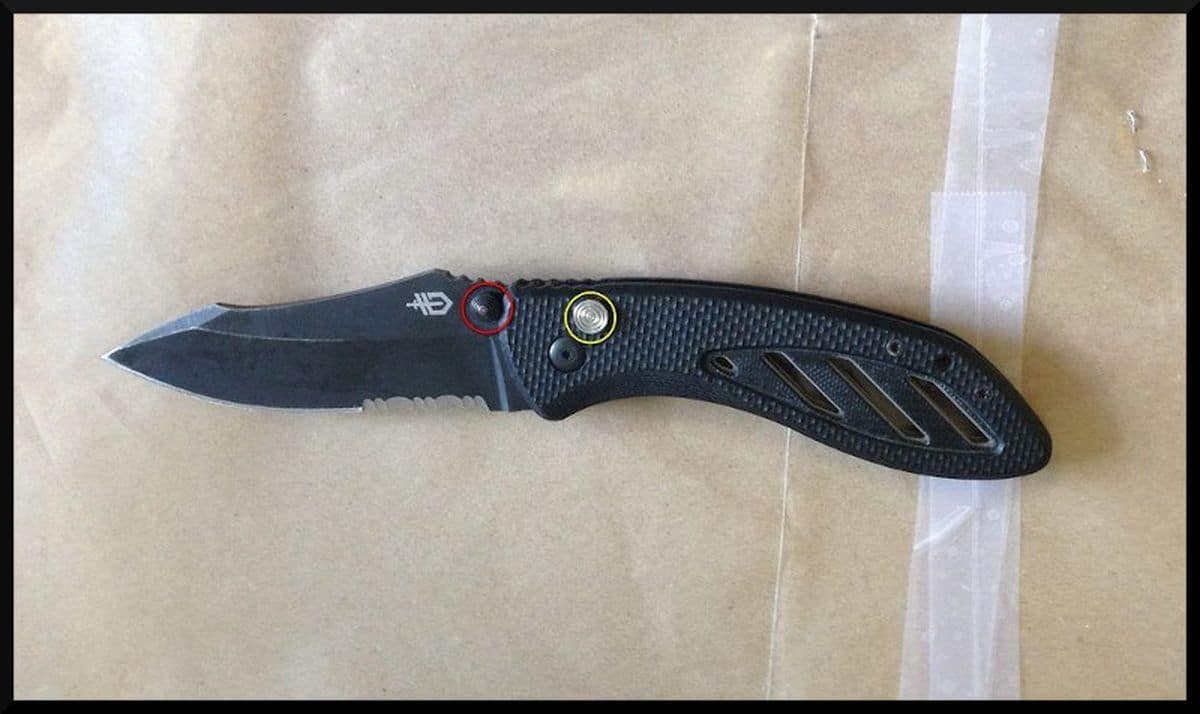

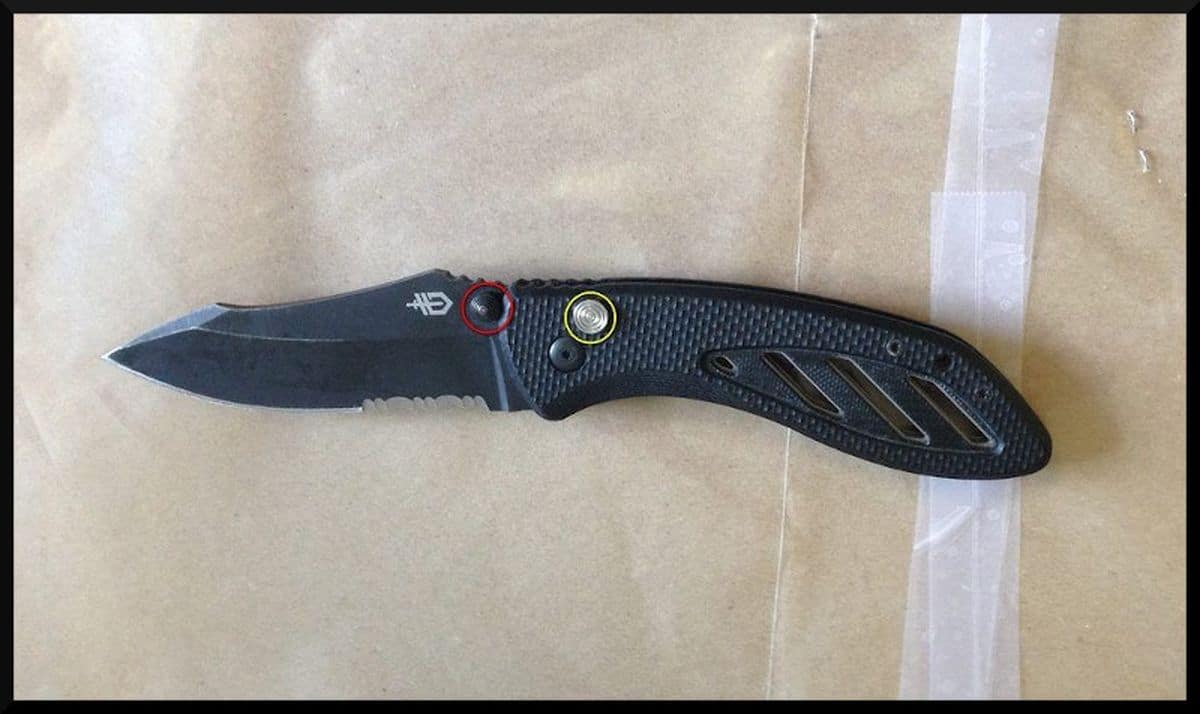

The knife in question was a Gerber Assisted Opening Knife. It’s pictured above in the closed position (and below in the open position).

Viewing the Knife

I viewed the knife at the District Attorney’s office.

The arresting officer demonstrated how it worked: as he pushed his thumb against the stud attached to the knife’s blade (circled in red in the photos above and below), the blade sprang open after rotating approximately 10 degrees from the closed position.

Definition of Switchblade

“Switchblade knife” is defined under Section 265.00(4) of the New York Penal Law as:

[A]ny knife which has a blade which opens automatically by hand pressure applied to a button, spring or other device in the handle of the knife.

Not a Switchblade

It turns out that my client’s knife doesn’t fit within the definition of switchblade.

The knife springs open from the locked-closed position – but only after thumb pressure is applied against the stud attached to the blade (circled in red in the photos). The stud’s location on the knife’s blade, and not in its handle, makes all the difference.

Though the knife has a chrome-colored button in the handle (circled in yellow in the photo immediately above), pressure applied to that button doesn’t cause the blade to automatically open.

Pressing that chrome-colored button unlocks the blade when it’s in the locked-open position, so you can manually fold the blade back into the handle. The chrome-colored button serves no other function.

So, the knife does not have a “blade which opens automatically by hand pressure applied to a button, spring or other device” that is located “in the handle of the knife”.

Therefore, the alleged switchblade isn’t a switchblade.

Always Examine the Switchblade

Because police officers frequently misunderstand the legal definition of “switchblade knife”, your lawyer should always examine the knife for you.

Your lawyer’s inspection might result in the case against you getting dismissed.

Free Consultation

Bruce Yerman is criminal defense lawyer in New York City. His office is located in Suite 1803 of 299 Broadway in Manhattan.

If you’d like a free consultation to discuss an alleged switchblade knife, or any other issue related to criminal defense or family law, call Bruce at:

Or email Bruce a brief description of your situation:

Leave a Reply